Pocket-sized

Tweet

I’ve been having a lot of “AHA!” moments lately about problems that I didn’t understand before, and I really love that feeling. On September 8th of this year, I had an “AHA!” moment about the JavaScript event loop, and the whole idea of Node.js finally made sense to me, which felt incredible. Recently, I’ve been having a lot of “AHA!” moments about structuring applications, especially when it comes to breaking things apart, why to break things apart, and where to break things apart. I have repeated the mantra of “Small modules” and “do one thing really well”, but I never really understood the benefits of it until very recently.

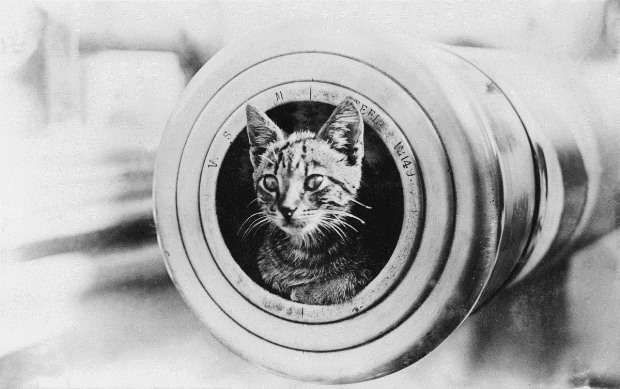

So here is my article on small things; my personal take on big words like monoliths, microservices, and modularization. I wish I had more time to write up code samples, or to make really engaging diagrams, but since it’s the middle of finals week, I will just do my best with descriptive analogies and vintage photos of kittens.

The bigger they are…

Over the summer, I wrote an AngularJS/Phonegap app that you could install on your phone to help you find nearby WiFi hotspots. When I was starting to develop it, I didn’t have very much experience wielding the power of AngularJS, and so took the approach that most beginners take, and threw everything into one great big controller.js file. All said and done, it was a 500 line file of all handmade sloppy code.

It was easy to build it this way. I didn’t need much time to get the app up and running, and had a lot of the functionality working right out of the box. If you are trying to create a quick mock-up or prototype of what you want to polish off later, building a monolith, where one master file takes care of almost all of the logic, can be really easy to get going. Things tend to gravitate this way for beginners, and in general I did not see a problem with doing it this way.

Issues started cropping up when I wanted to start testing the app though, and performance was taking a huge hit from the Franken-controller. The app was slow and buggy, and I could barely remember which line was controlling what. It felt like looking for a working pencil in a junk drawer.

Too Small to Fail

My brother Jonah told me “You’re Jake Pruitt, you’re too small to fail!” when I told him about all of my finals coming up. I like this line a lot; I think I should make stickers that say it and put them everywhere. “Too Small to Fail” is not only ironic, but also very applicable to the world of software architecture.

A long time ago, there were a lot of smart people who came up with ideas about computer programming, and one of those people was Thomas J. McCabe Sr.. He proposed that programs should be kept very simple, and there should only be a maximum of 10 decisions made in any one program. If a routine, or module, exceeded that number, some of the logic should be condensed into a submodule. This would allow programs to be more easily testable, and more maintainable across teams. Some studies have shown that having fewer decisions in any one module will lead to less bugs.

Another really smart programmer by the name of David Parnas was one of the first proponents of modularizing programs. He advocated for hiding module-specific information within the module and loosely coupling modules so that they could easily adapt to change within a program. Many of his ideas were used when the Law of Demeter guideline was created, which is also called the “principle of least knowledge.”

So that was a lot of random facts, and if you were brave enough to read through those two paragraphs, you will start to see where I’m going with this idea of small pieces rather than one big pile of code. Think of it this way: every day, millions of people have to go from their nice warm beds to their office miles away. Now, there is no authority above us who directly tells every person where to go, when to go, and which direction to go for us to get to the office. Every person kind of just knows how to drive, and knows what they need to do and how to operate with the drivers around them. It’s a miracle that so many people get to work every day, even without anyone telling them exactly what to do.

If you are building a very modular system, with small pieces combining to do a lot of work together, it’s a lot like having tons of individual cars operating independently to get everyone to their destinations. Smart people, dumb roads. This is very different from air traffic control, where every airplane has a very specific schedule, and every controller knows where every plane is. Smart controllers, obedient pilots.

I am not sure if this analogy is the most appropriate way of explaining modularity. There are millions of analogies to use, like the power rangers combining to fight the giant villain, or schools of fish outsmarting barracudas. Whichever analogy you choose, you can begin to see that distributing systems from the beginning can be very useful and often critical to the long term success of a project.

Tweet