Probably

Tweet

What is a probability? Does that question ever keep you up at night? When you think of probability you probably think these three things:

- Man, if I were really good at doing probabilities in my head, I’d be able to win so much money at casinos

- Probabilities can’t be that hard, but I remember really hating it in high school. Something about different colored marbles in a bag…

- (you wake up 8 hours later) oh, what was I thinking about last night?

And that’s good. That’s all that any sane person should have to do with probabilities. I, however, decided to take a 400 level math course in probability, and it has completely demolished my self-esteem as a mathematician. In preparation for my upcoming final, I’m going to write about some general theories of probability, and try to solidify a few of the ideas in my head.

A coin and a baby

I will start by asking a simple question that our professor asked us on the first day:

What is the probability that this coin will land heads up?

“Fifty-fifty” was the typical answer, and when asked why, the student typically replied, “If you flip it a million times, it will come up heads 500 thousand times.” And the professor said, “I’m not asking you how many times it would come up if flipped a million times. I want to know about this time. Right now. What does a 50-50 probability mean now?”

To clarify, he asked, “Let’s say you’re an expecting mother, and you ask your doctor the probability that your baby will be a boy, and he says 50-50. You can ask him what that means and he says, ‘If you give birth to this baby a million times, it will be a boy 500 thousand times.’” This was the point that the professor was trying to make. We weren’t looking at the relative frequency of repeated trials, we wanted to know information about a single event. More than that, we wanted to quantify that information.

Bayesian - Supporting evidence

In pure mathematics, there is a lot of use of “If A, then B” statements. These implications are only one-directional, meaning that knowing B does not imply knowing anything about A.

All of probability lies on one slight modification of this idea. While we cannot imply that A is true from knowing B, we can say that it is more plausible. For instance, if it is raining, then there will be small taps on your window. That is a true statement. In pure mathematics, if you hear small taps on your window, that does not tell you anything about whether or not it is raining. In probability, you can say that small taps on your window make rain more plausible.

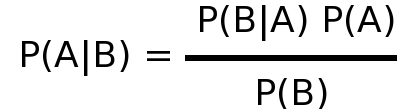

That is the foundation of Bayesian probability. All probabilities are conditional upon the evidence that you have, and you are constantly analyzing the effects that new data have on the plausibility of certain events. The math involved is rather tricky, but essentially comes down to one simple formula, Bayes’ Theorem:

| This says that the probability of an event A being true, like “It’s raining outside”, given some evidence B, like “I hear small taps on my window”, can be expressed as the product of the probability of rain without hearing taps (P(A)) times the probability of hearing taps when it rains (P(B | A)), divided by the probability of hearing taps (P(B)). While conceptually simple, the implications of this formula can be hard to pin down in practice. It can be especially hard to determine the likelihood of it raining right now, without any of the evidence that you have gathered. There are many debates within the scientific community about the appropriate way to choose that prior probability distribution. If a paper includes a Bayesian analysis, most of the defense will need to be on how the researcher determined the prior distribution. |

Subjective - There’s no such thing as fairies

Another school of thought on probability is that there is no such thing as a certain future event, and there is no such thing as a true probability of an event occurring. Everything is uncertain, and everyone places different subjective likelihoods on those events. The probability of the coin coming up heads is simply the amount of money you would be willing to bet on the coin coming up heads. If you bet twice as much money on heads than on tails, then you don’t believe that the coin will be 50-50, you believe it will be 66-33. There is no such thing as THE probability of an event. Everyone has a different probability for every event.

I personally find this interpretation to be the most believable. It can be a real mind-bender when you look at the implications on things like gravity. If I hold a pen in the air and ask you the likelihood of it falling to the ground when I let go, you will probably say 100%. But if I offer you $1 million if it does anything but fall, and $0.01 if it does fall, would you take those odds? What if I offered you every dollar in the world? What if I offered you supreme domain over the entire world and everything in the universe? Would you maybe, just maybe, bet against gravity, in the off chance that it doesn’t work this time? Because everything is uncertain, even gravity working is uncertain until it happens.

Subjective probability is often used in game theory, where every action that you perform is based on the probabilities you assign to the actions of your opponent. And these probabilities are all subjective, but they are still rather measurable, since the actions you take reflect the probabilities you believe in. For instance, in rock-paper-scissors, you play one of the actions based on which action you believe your opponent is most likely to take.

In the end, my predictive powers have not improved very much from taking these classes, but I know that if I do not study tomorrow, I will probably not do so well on the final exam. So I am going to bed now to get ready for a day of probability theory. Good night!

Tweet