Modulo

Tweet

In every initial walkthrough of a programming language, one of the first mathematical operations they highlight (after +, -, * and /) is modulo (%). I always wondered why this was a part of every language, and important enough that they made it a highlighted part of introductory tutorials. After taking a course in cryptography, though, I have learned that the basis of nearly all cryptosystems rely on the modulo function and its special properties.

Here is a real introduction to the power of modulo.

A String Around Your Finger

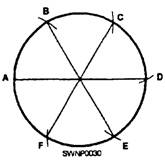

When my professor described the modulo function, specifically 8 % 6, she described it very visually. She said, “Imagine you have a tetherball pole, or your finger, and it’s 6 units around,” and she drew a picture that looked like this on the whiteboard:

“Now if you start at point ‘A’, and take a string that is 8 units long, and wrap it around the pole once, you realize that the string would end at point ‘C’.” She drew a coil clockwise around the circle that overlapped itself for two units. “This overlap, the distance from ‘A’ to ‘C’ is the leftover from dividing 8 by 6. 8 % 6 = 2.”

Most people refer to modulo as the remainder function, which is exactly what the function does. If you divide 8 by 6, you have a remainder of 2. If you divide 153 by 2 you get a remainder of 1.

TLDR: The formal definition of modulo, in technical terms, is this:

An integer a is congruent modulo n to b (

a % n = b) if and only if there exists an integer k such that a = k*n + b.

Carousel Wrapping

I have used the modulo operation many times in the wild while doing front-end web development. One problem where I used it was in creating a looping carousel for a hero banner. The hero had 3 images, and after the third image, I needed to rotate the carousel back to the first image. Now, the problem of whether you should even be using a carousel is entirely another question. Our problem was implementing it:

<div id="homepage_slides">

<img class="slide" src="/images/image_1.jpg" />

<img class="slide" src="/images/image_2.jpg" />

<img class="slide" src="/images/image_3.jpg" />

</div>

<button id="homepage_slides_prev">Prev</button>

<button id="homepage_slides_next">Next</button>

We needed to change the index of the current image when the user clicked the “Next” button. So we select the elements in JavaScript, and when the user clicks the next button, we increase the index by one and call a function with the new index to rotate to:

var index = 0;

var next = document.querySelector('#homepage_slides_next');

var slides = document.querySelectorAll('#homepage_slides .slide');

next.addEventListener('click', function() {

// Not going to work:

index++;

// Some fancy carousel function that takes our slides and an index

rotateToIndex(slides, index);

});

While this seems like a good idea, we are actually going to throw a RangeError exception when our index increases above 2. That is because we don’t have a fourth image in our carousel. Therefore, we need to change our line index++ to:

index = (index + 1) % slides.length;

This allows our index to rotate around to 0 again when we try to exceed the indices of the array. We can think of this like the string analogy: after the last image, we want to go back to the first element of the array. We want our counter to wrap around. If we are at index = 2 and “Next” gets clicked, then (2 + 1) % 3 = 0 since the remainder of 3 / 3 is zero.

Ceaser Cipher

One of the most basic ciphers in cryptography is the shift cipher, also known as the Ceaser cipher (since Julius Ceaser used it in his correspondences). The basic idea is to take a string and shift every letter to the letter that is a given distance in the alphabet away. For instance, if you had a shift cipher with the key “4”, “a” would shift to “e” and “o” would shift to “s”, since they are four letters away in the alphabet.

But what if you have the letter “z”? In that case, you want to wrap around to the beginning of the alphabet. In a shift of 4, “z” would become “d”. Let’s take a look at the code:

var abc = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz";

var message = "thursday";

var key = 4;

var ciphertext = message.split('').map(function(char) {

var charNum = abc.indexOf(char);

var shiftedNum = (charNum + key) % abc.length;

return abc[shiftedNum];

}).join('');

console.log(ciphertext);

// => "xlyvwhec"

The use of modulo is present even in this very basic cryptosystem. And believe me, cryptography only gets harder from there.

I hope this helped you put modulo in the frame of an actual application. Let me know if you want to learn more cryptography in later posts!

Tweet